J & M Craig Kilmarnock brick found in USA

— 17/09/2023Found by John Lowe in Long Island, New York State, USA. J & M Craig, Perceton Fireclay Works, Dreghorn, Ayrshire. . . . .

J & M Craig, Dean, Hillhead and Perceton Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock and Longpark Pottery, Kilmarnock.

(Note – SBH – I have created separate pages for Perceton, Dean, Hillhead and Longpark. Where information does not relate to a particular works, such as Craig family history, I have added it to the Perceton page.)

Below – Dean Quarry and J & M Craig Works.

Below – Source unknown – For a long time Kilmarnock was mainly celebrated for the production of bonnets, carpets and shawls, but of late years other trades have sprung up, such as engineering shops, wincey, tweed, and lace manufactories. It is also justly celebrated for the manufacture of fire bricks and other fire clay goods. This latter branch of industry, at the well-known works of Messrs. J. and M. Craig, is the subject of the present article.

The record of the enterprise of this firm might almost be said to be identical with the history of fire clay manufacture in Scotland. More than half-a-century ago — as far back as 1828 — the business was commenced at Dean Quarry, near Kilmarnock, by Mr Matthew Craig, father of the gentleman who is now the senior partner of the present firm. It was a small beginning. The entire plant consisted only of a pair of rollers for crushing the clay, one kiln for burning the bricks, and the necessary moulds, tools, &c. These gave employment to three men and two boys. At first, the motive power was communicated to the rollers from a rotary gin, but this soon had to be replaced by a steam engine with an increased plant. The operations of the firm so limited at the commencement, since then have been gradually but steadily extending and increasing, and they are now carried out on a very extensive scale indeed, in large works at Hillhead and Perceton, covering about six acres of ground and employing nearly four hundred men and boys.

When the Dean Brickwork was commenced there was then no other fire clay work in Ayrshire, and, excepting one or two near Glasgow, none in all Scotland. Now there are nearly a dozen works in Ayrshire, the same number in other parts of the West of Scotland, and about half-a-dozen works in the East country.

Fire clay manufacture at the Dean in those early days was limited to common building bricks—upon which, by the way, a duty of six shillings per thousand was then levied by the government—but by and by the clay was found to be very suitable for the production of other goods, such as compressed tiles for paving the floors of kitchens, entries, &c., troughs for cattle-feeding purposes, and salt-glazed pipes for sewers and for carrying water: to the making of which it was accordingly applied.

By this time several fire clay factories had been started in Ayrshire and various parts of Scotland, but the tact and energy of Messrs. James and Matthew Craig—who had succeeded their father—had gained the confidence of a large number of customers, and their business continuing to increase, they found it necessary, in 1861, to purchase the Hillhead Fire Clay Works, and again in 1862, to take over the Perceton Works. Largely increased means of supply were accompanied and followed by increased demand, and notwithstanding all the fluctuations of trade, the various goods made at these works have been in such constant request, that even with very large additions and improvements to the works of late, some difficulty is still felt in supplying all the orders.

Messrs. Craig have always been very prompt in discerning and opening up new branches in the manufacture of fire clay, improving the old methods of working, and in perfecting the quality of the goods turned out, and are now generally acknowledged to be at the top of the tree in the fire clay line – occupying in Scotland a position somewhat analogous to that of the Messrs. Doulton in England.

The process by which raw, worthless-looking clay, is transformed into valuable building material, or into more expensive and beautifully enamelled goods, is a very interesting one.

The fire clay is found underlying the coal in seams of from eighteen inches to three feet thick and is wrought along with the coal. At Hillhead, four pits supply the material and the fuel, which are conveyed in trucks by rail to the adjacent works. Here the clay is first submitted to the pressure of a grinding mill, and by the large iron wheels revolving on perforated plates, it is quickly reduced to a fine powder. From the grinding mill, it is raised by elevators to a “worm” which transfers it to the mixing pans, where, by the addition of water it is rendered plastic, and ready for the moulder’s benches. In the case of bricks, the clay is cast by hand in strong wooden moulds; and, if intended for common building purposes, the bricks are then dried in stoves, preparatory to being more thoroughly dried and burned in the kilns. If, however, it is intended that the bricks are to be glazed or enamelled, the process is a longer and more intricate one. After having the superfluous moisture removed in the stoves, they undergo an enormous pressure, under the pressing machine, and are then “dressed” by another machine, and after being carefully “finished” by hand, they receive a coat of the enamel in the liquid state and are then ready for the kiln. There the heat is at first applied very gradually but is steadily increased, until it reaches sufficient intensity to thoroughly incorporate the glaze with the body of the clay.

When taken out of the kiln the enamelled bricks are of a brilliant white colour, and we understand they are perfectly impervious to weather, non-absorbent of chemical or other vapours and incapable of being permanently soiled or dirtied. They are admirably adapted for lining back walls, and “wells,” in buildings where reflection of light is valuable, also for lining common stairs and closes, public baths, urinals, water-closets, passages and wards in fever and other hospitals; and generally for any purpose, where it is important to have beauty and lightness, combined with durability, non-absorption of vapours, and easiness to keep clean.

Coloured and printed enamelled bricks are produced in a variety of tints. The enamelled washing tubs, and enamelled sinks for kitchens, butler’s pantries, &c, are also moulded by hand and are very carefully finished and glazed, in the same manner as the enamelled bricks. These washing tubs and scullery sinks have a beautiful appearance; almost equal to porcelain, which, we believe, they greatly excel in strength and durability. Messrs. Craig informs us they are now extensively used in houses of the better class.

**********************************

J & M Craig Ltd, Kilmarnock – source Kenneth W Sanderson. An advertisement in Slater’s Directory of 1867 claims that the company was established in 1831, which would pre-date the Garnkirk Fireclay Company of Lanarkshire. This claim is probably based on the Dean Firebrick & Tile Company which was making firebricks on the lands of the Duke of Portland, east of Kilmarnock about this time. The Statistical Account of 1845 states that the parish of Kilmarnock was making considerable quantities of firebricks which were sold for £4 per thousand. Hunt’s Mineral statistics of 1858 records that the brickworks produced 4,365 tons a year of firebricks, chimney cans, pipes and retorts. The Dean area contained an excellent supply of freestone, and this quarry expanded to six acres to supply much of the stone used to build Kilmarnock, and in doing so swamped the fireclay works. The Kilmarnock Standard of 13th April 1872 has an interesting article on Dean Quarry and states that the first regular lessee was a Mr Law of Messrs Brown & Howie and that the quarry later passed into the hands of Martin Craig, senior, who with his two sons founded J & M. Craig.

The Perceton Fireclay Works at Dreghorn were taken over by J & M. Craig in 1863. Previously in 1858, they were owned by the freeholder and manufacturer, P. & M. MacReady who produced firebricks, pipes and retorts amounting to 6,552 tons a year: a substantial quantity for those days. They had agents in Glasgow, Dundee, Perth, Annan, Ayr and Ardrossan, which indicates the local nature of the business at that time.

The Hillhead Fireclay Works at Kilmarnock was taken over by Craigs in 1867 from John Gilmour & Company, who had owned it from at least 1858. Craig now became the largest firebrick company in Scotland, surpassing the Garnkirk Company; however, they were in their turn soon to be surpassed by the Glenboig Union Fireclay company which was formed in 1882.

The expansion of Craigs continued with the establishment of the Longpark Sanitary Pottery near Hillhead. The Muirhouse Brickworks near Irvine and the Lillieshill Fireclay Works near Dunfermline were brought into the group in 1896 when the company was incorporated as J. & M. Craig Ltd. The capital was £50,000, of which well over half was held by James Craig and his sons. A petition was brought before the Law Courts in June 1906 to dissolve the company as £45,000 of debentures were due for repayment. Whilst most of the holders were agreeable to extend the term, a minority refused. Assets were estimated at £127,427, and liabilities at £70,345, so the surplus exceeded the share capital: This led to a reconstruction of the company and J. & M. Craig (Kilmarnock) Ltd. was formed with a capital of £5,000 £1 ordinary shares and 15,647 £1 preference shares. The company continued to trade up to 1915 but was liquidated the following year.

1831 – Possible date the firm started. Then known as the Dean Firebrick & Tile Company and run by Matthew Craig Snr, father of J & M Craig.

1855 – 1857 – Dean Quarry – An extensive freestone Quarry worked by Messrs. James & Mathew Craig and is the property of the Duke of Portland and J.G. Parker Esq. of Assloss (the property boundary or March running through it) There is a seam of coal about 16 inches thick and about 4 feet from the surface runs through it which dips greatly to the Westside as the ground rises. Coal is also found in it at a considerable depth, there is a new shaft sunk from which they obtain a sufficient quantity for carrying on the fine brick & tile works connected to it.

1858 – Mineral Statistics of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for 1858 – Dean, clay of coal measures. Name of freeholder – Duke of Portland. Manufacturer – J and M Craig. Manufacture – bricks, chimney cans, pipes, retorts &c. Estimated 4,368 tons annually.

09/06/1858 – Glasgow Herald – Glasgow Agricultural Society’s Show.

Feeding troughs for pigs – 1st William Smith, Hurlford Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock and James and Matthew Craig, Dean Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock commended.

Feeding troughs for sheep – 1st William Smith, Hurlford Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock.

Churn worked by hand – 1st James and Matthew Craig, Dean Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock.

Traverse divisions – Rack and manger for farm stables – 1st William Smith, Hurlford Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock.

Tile and pipes for field drainage – 1st William Smith, Hurlford Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock.

Glazed socketed pipes for sewerage – 1st William Smith, Hurlford Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock. James and Matthew Craig, Dean Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock commended.

Below – 12/06/1862 – Perthshire Advertiser – Alexander Campbell is an agent in the Perth area for J & M Craig, Dean, Hillhead and Perceton, Kilmarnock.

Below – 02/05/1863 – Ayrshire Express – Ayrshire Agricultural Association.

Below – 02/06/1865 – Elgin Courier – Advert for J & M Craig, Dean, Hillhead & Perceton Fire Clay Works (The same advert is shown again in the Elgin Courier on 29/06/1866).

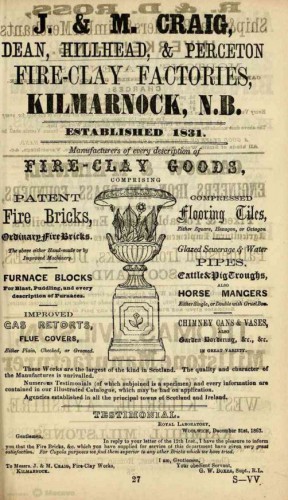

Below – 1867 – Advert J & M Craig, Dean, Hillhead & Perceton, Kilmarnock. (Apologies for the double print).

Below – 1868 – J & M Craig, Dean, Hillhead and Perceton Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock.

30/04/1870 – Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald – Ayrshire Agricultural Show – Stand no 22 – Messrs J & M Craig, Dean, Hillhead and Perceton fire clay factories, Kilmarnock. Judges awarded a medal for a collection of cattle troughs, horse mangers, milk coolers, sheep dipping trough and a collection of statuary, flower vases etc.

1872 – J & M Craig, Coalmasters and Fire Clay Manufacturers, Dean, Hillhead and Perceton Fire Clay Works and Hillhead Colliery. Office Hillhead.

Below – 20/04/1872 – Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald – The Dean Quarry – 2 weeks ago this quarry ceased to be worked.

14/08/1880 – The Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald – The Industries of Kilmarnock – Messrs J & M Craig’s Fire Clay Works – Since the time when the Israelite’s were compelled to make bricks without straw by their hard taskmasters, the making of bricks has continued to be a very primitive looking business. Within recent years some attempts have been made to supersede the common-mode by machinery, but they have failed both in point of quality and economy and bricks continue in most places to be made by hand. In other respects, however, fire-clay manufactures have greatly improved, and innumerable useful and artistic objects are produced from common clay. The beautiful figured vases, for instance, which adorn our public park, and are invariably to be found in every flower garden, are a slight indication of the useful and beautiful articles that are made; and we are credibly informed that in the matter of kitchen sinks, troughs, &c., the enamelled fireclay manufactures are rapidly pushing the cast iron articles out of the market. That is only one example of the direction in which this industry is moving. There are over 100 fire-clay manufactories in Scotland, and that of Messrs Craig including their works at Hillhead and Perceton is perhaps one of the largest. The Hillhead work alone covers between four and five acres of ground. It will be within the knowledge of our readers that at the beginning of the century, the father of Messrs Craig was quarry master at the Dean to the Duke of Portland. It was here, it may be said, that the present firm took its rise. In the year 1828, Mr Craig first began to make bricks, and from that date up to the time when Messrs Craig bought the Hillhead and Perceton Works, the business of brick-making was carried on at the Dean Quarry. About 19 years ago, when they acquired those Works, there was nothing manufactured but common bricks and tiles, but under the new impulse received from them, the more artistic branches of the trade began to be cultivated. At Hillhead all the enamelled brick work is manufactured; but the vases and other artistic works are made at Perceton, the clay their being of a more suitable nature for such articles. The principal articles manufactured at Hillhead, besides the common bricks and tiles, are chimney cans, garden edging, sewer traps, pickling pots, cattle troughs, and white enamelled bricks, sinks, edgings for gardens, &c., the largest of all being gas work retorts. They also occasionally manufacture full-length human and animal figures. The firm does an increasing business in the white enamelled sinks; while the enamelled edging is coming into general use everywhere its effect amid flowers and shrubs being alike refreshing and artistic, as is shown in the new cemetery. The clay used in the Hillhead is wrought out of pits in the same manner as coal. The various pits around the works have a clay, as well as a coal seam, the former being found under the latter; and there is a line of rails connecting the pits and the brick-work, besides a junction with the mainline of the Glasgow and South-western Railway. When the clay comes from the pit it is a hard, dry substance, having not the slightest cohesion. It is finely ground into fine dust in a powerful mill, consisting of two large iron rollers travelling around a circular trough. This mill is enclosed in a large building, and is connected with an ingenious set of machinery by which the clay dust, when sufficiently ground, passes through a sieve, and the refuse, or the part that requires to be re-ground, is thrown back into the mill, into which water is run, until the clay is wrought up to the requisite softness and cohesion, after which it is ready for use. Bricks are very simply made, one man being able to make 3000 or 4000 a day on piece-work. The moulder stands at a table, on one end of which is heaped up a load of clay. Before him, he has the mould, in shape like a hollow box with the ends knocked out. The mould is wet, and the man takes a piece of clay and presses it with his hands, and then removes the superfluous clay by drawing a smooth piece of wood over the mould. A boy immediately lifts the mould away, having already placed another mould on the table ready for use. In this manner, the work goes on very rapidly, one man generally requiring the two boys to lift the bricks and place them on the floor. The pipes, again, are made by the clay being pressed down through an iron die by a steam revolving shaft. The pipes are cut off, by a self-acting knife in lengths of three feet, and are manufactured at the rate of 150 an hour. The flanges are formed separately in stucco moulds and attached to each of the pipes. The rooms in which these are manufactured are all laid below with steam pipes, and the bricks lie there for a short time until they are ready to be placed in the kiln. The floor bricks and those that have to be examined, pass through a pressing machine, equal to a weight of six tons, before passing into the kiln. There are altogether twelve kilns in the Hillhead Brickworks, and the bricks or other articles are so placed in these that the heat passes between each. Each kiln will hold perhaps about 10,000 bricks, and they remain in for twelve days. The other description of work we saw going on were equally simple, although requiring some little practice to perform. The four sides of the troughs, for instance, are moulded separately, and then placed together within perhaps a couple of inches of each other at the corners. The moulder then takes a piece of clay and fills them in at the corners, solders them together as it were; and in the course of half-an-hour the moulds can be taken off, and they are enamelled inside, and afterwards sent to the kiln. All this class of work is cast in stucco moulds. As we have said, the most of the fancy work is manufactured in Perceton, and as what is called terra cotta is coming greatly into fashion for architectural facings, &., there is little doubt that in this line the trade has a progressive future.