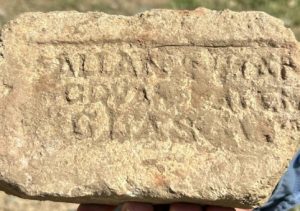

This brick was found on the site of the old Jenny Lind Brickworks, Near Motherwell, Lanarkshire adjacent to the old site of the Ravenscraig Steel Works.

It is a dense heavy brick and is believed to have been manufactured by Harbison Walker, USA.

History – Harbison-Walker Refractories Company (Harbison) is the world’s leading supplier of refractory technology, products and services (refractories are nonmetallic materials suitable for use at high temperatures in furnace construction). The company manufactures more than 300 refractory brands, and mines and processes ores for both internal use and for sale to third parties. Harbison’s worldwide presence of affiliates, licensees, and international sales agents enables Harbison to directly service the pyro-processing industry globally. The company controls over 65 per cent of the raw materials it consumes, making it virtually invulnerable to worldwide supply fluctuations.

The refractories industry was born with the advent of the steel-producing Bessemer Converter served by blast furnaces capable of melting metal. The Bessemer process was an early method for making steel by blowing air through molten pig iron, whereby most of the carbon and impurities are removed by oxidation. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, European companies began manufacturing firebrick for the construction of walls for blast furnaces, kilns, crucibles, and ladles. The Industrial Revolution ignited a manufacturing boom in America for the production of machinery, glass, and forged metals, giving rise to the need for massive quantities of firebrick. Emerging technology industries created new markets for specialized refractories. Seizing upon the opportunities of the time, the founders of Harbison determined to develop products that would accommodate the growing marketplace.

A Post-Civil War Venture

The Harbison-Walker Refractories Company (Harbison) was organized in 1865 by J. K. Lemon and originally operated under the name of the Star Fire Brick Company. With a capitalization of $8,000 the venture was financed by ten partners who had no knowledge of brickmaking. The first plant utilized raw materials from clay mines at Bolivar, Pennsylvania, which went into the making of Star brand fireclay brick. In 1875 the original partnership became known as Harbison and Walker, and was later reorganized into the Harbison-Walker Refractories Company in 1902, led by Samuel P. Harbison and Hay Walker. At the outset, Samuel Harbison had been hired as company secretary but soon assumed responsibilities for organizing a systematic investigation of fire clays and their suitability for refractory brick uses. Walker was the other remaining original partner and functioned as bookkeeper as well as the person responsible for the study of plant efficiencies and kiln records that chronicled each kiln’s reject loss in burning. Between 1909 and 1910 the Harbison-Walker Research Department was formally established, with studies conducted at the company’s Hays Lab on the Monongahela River. Their research contributed to the development of super-duty silica refractories largely useful in the steel industry, special fireclay and super-duty fireclay blast furnace refractories, forsterite refractories for glass and other industries, new types of basic refractories especially adapted for the lining of rotary kilns, open-hearth steel furnaces, copper converters, and many other furnaces.

Dawn of the 20th Century: Supplying U.S. Steel

Refractories were made in the form of bricks of various sizes, but mortars and special shapes were also important in company product lines. Refractories are usually a light, buff color and are distinguished from ordinary building bricks by their composition of high silica and alumina clays and by being fired at much higher temperatures. These products are resistant to thermal stress and chemical abrasion, and play a fundamental role in many kinds of industrial production, particularly within the steelmaking industry. The company’s primary customer was Andrew Carnegie’s iron mills, and Harbison’s development shadowed his. According to Kim Wallace in Brickyard Towns, A History of Refractories Industry Communities in South-Central Pennsylvania, “In 1902, one year after the merger of Carnegie’s holdings into the U.S. Steel Corporation, the Harbison and Walker Company orchestrated a merger that brought its holdings to thirty-three plants and thousands of acres of clay mines.”

In 1905 the company began using steel moulds instead of wooden moulds in the making of byproduct coke ovens and other shapes. It became the first U.S. company of its type to use and develop the continuous tunnel kiln for the burning of silica brick when it erected its East Chicago, Indiana, kiln in 1927. Harbison held the license on the discovery that steel or iron sheets heated between magnesite bricks would oxidize and bond the brick together into a solid structure. The company developed this process until it came out with its “H-W Matalkase,” which produced the first chemically bonded magnesite-chrome refractory.

In further expansion developments, Harbison assumed ownership of the Northwest Magnesite Company in 1923, selling off 40 per cent of that venture three years later. Harbison expanded into Canada and became that country’s largest refractory producer when it combined the assets of three magnesite producing companies and organized them into Canadian Refractories Ltd. in 1933.

World War II-Era Fostered Expansion Explosion

Entering a new market, the company began producing kiln devices for the pottery industry and other applications with the purchase of the Loughan Manufacturing Company of Ohio in 1947. Another milestone was the company’s contract to supply materials for the construction of the world’s largest blast furnace at the Zug Island Plant of the Great Lakes Steel Corporation in 1955. Throughout the decade the company and its subdivisions grew to operate 33 plants in 12 states and Canada, producing refractories of silica, fire clay, super duty high alumina, magnesite, chrome, forsterite, plastic fire brick, castables, insulating refractories, mortars, and ramming materials. During this period Harbison initiated a program of modernization and new construction, including the construction of 32 continuous tunnels and a renewed emphasis on quality control.

By the mid-20th century, the south-central Pennsylvania refractories business was dominated by three companies which had grown through a series of mergers. Harbison emerged as the company with the largest holdings. From 1955 to 1965 the company established its first overseas manufacturing subsidiary in Lima, Peru, called Rafractarios Peruanos, S.A. Their principal products were fireclay, silica, and basic refractories. Within the year, Harbison added Frabrica de Ladrillos Industriales, S.A. in Monterrey, Mexico, to their operations, naming the venture Harbison-Walker-Flir. Six years later a Venezuelan affiliate company, Cermica Carabobo, C.A. was added to the company’s production facilities. Harbison invested $73 million in expansion during this time period, including a $2 million modern Garber Research Center located in Pittsburgh. Harbison also signed a joint-venture agreement with the Carborundum Company of Niagara Falls, New York, in 1960, and in 1966 the Tanner Plating Company of New Castle, Pennsylvania, was acquired, adding the services of complete industrial hard chrome plating, grinding, and honing. A further South American development included the addition of a Chilean affiliate, Refractarios Chilenos, S.A. Moving into Australia the following year, the company acquired a subsidiary in Unaderra, New South Wales, Harbison-A.C.I. PTY. Ltd.

Continued Overseas Expansion in the 1960s

In 1967 Harbison merged with and became a division of Dresser Industries of Dallas, Texas, a company that principally catered to the oil service industry. The acquisition offered the needed diversity to buffer the company during slack growth periods, and also accelerated the company’s move into non-steel related industries. A new company was formed four years later when Dresser signed a joint venture refractory products manufacturing agreement with a West German company, Martin & Pagenstecher GMBH. The new company, named Magnesital-Feuerfest, was stationed in the Ruhr district in a newly constructed $10 million plant. The Harbison facilities were operating at full capacity during this period and managed to cope with energy shortages and shortages of many of the raw materials needed for production. The company supplied refractory products and high purity fused grains to the electronics, chemical, fibreglass, and foundry industries. They sold improved high-alumina products to the non-ferrous industry and resin bonded magnesia-carbon brick for basic oxygen converters and electric furnaces and special magnesite refractory products. The company continuously improved upon technological means of producing more and more specialized products for the changing steel industry.

Downsizing in the 1980s

In 1973 Dresser expanded into Iran, establishing a new company, Iran Refractories Company (IREFCO), centred in the hub of the Iranian steelmaking industry. Their newly constructed $5.5 million plant began operating in 1976. After peaking in its cycle of capital spending, Harbison experienced a time of declining production that lasted into the 1980s, shadowing an overall industry decline. Changes in production technology affected the major industries that used refractories, challenging Harbison to completely restructure its facilities. Harbison acquired a fused silica production facility in Calhoun, Georgia, in 1976, which enabled the company to diversify into a new product line.

In 1992 the INDRESCO Company Inc. was created as an independent public company in a spinoff to shareholders by Dresser Industries, Inc. INDRESCO raised $92 million by reducing partnership in a joint venture with Komatsu and selling its European compressor business, with a plan to develop a new enterprise with a new growth strategy. The top refractory producer in Mexico was acquired, resulting in enhanced capability in processing and recycling. The remainder of the Komatsu joint venture was liquidated and a leading Chilean refractory producer was acquired while the company began showing increased sales and expansion. Concentrating on overseas expansion in 1995, INDRESCO created an International unit within the refractories division. The following year a new parent company was formed, structured as a holding company named Global Industrial Technologies, Inc.

Harbison entered the 1990s as a worldwide leader in new technology refractory products and service. The company was honoured with the receipt of the “E” Award, in recognition of excellence in exports and the introduction of a new generation of magnesite-carbon, ultra high-alumina brick, and speciality products. Two marketing arms, the Iron and Steel Marketing Group and the Industrial Marketing Group meet the refractory needs of these diverse segments separately. Other company delineations accommodated the specialized areas involved in researching and understanding a new generation of refractories of heat processing industries, which grew to include waste incineration, recycling, the conversion of steam to energy, carbon black for automobile tires, cement, and virtually every other process related to industrial boilers or furnaces.

The mining and minerals unit primarily produced high-purity magnesite, which was used in the manufacture of premium refractory items. Although the unit was formed with the intention of supplying Harbison’s business, the company also began selling raw materials to refractory manufacturers worldwide. With just 20 producers of these supplies worldwide, the company sold about 11 per cent of the world’s total high-purity magnesite (approximately 1.5 tons).

1996 and Beyond: Aggressive Capital Spending

In 1996 Harbison booked the largest project sales order in its history, a $25 million contract to provide refractory products for 268 new coke ovens being constructed in Indiana. The Sun Coal and Coke project at Indiana Harbor in East Chicago, Indiana, required 73,000 metric tons of Harbison’s premium silica and fireclay based refractory products. Also in that year export sales reached $25 million, with shipments to 53 countries. New sales offices were established in Singapore and Milan to facilitate progress in penetrating markets in southeast Asia and Europe. Over 25 per cent of refractory sales for the year were from products less than five years old, confirming the commitment to an aggressive new capital spending plan of more than $24 million for research and development for the following year.

Global Technologies revised its businesses into five segments: Refractory Products, Minerals, Industrial Tool, Specialty Equipment Products, and Forged Products. In March 1997 Harbison entered into a joint venture agreement with the Siam Cement Group to develop, build, and operate refractory plants throughout Southeast Asia. In addition, the company began negotiating the formation of a joint venture in the People’s Republic of China to manufacture refractories for use in China’s coal gasification industry, which was scheduled to begin in 1998. Additionally, the parent company purchased the Refractarios Lota-Green Limitada and refractory related assets of Concepcion, Chile, for $13.6 million. Combined with its other existing Refractarios Chilenos S.A. business in Santiago, Chile, the two companies became known as RECSA-LOTA and gave Harbison a significant market share in Chile. The alignment helped RECSA to win its largest contract in history: an agreement to supply $27 million of refractory products for Compania Siderurgica Huachipato, the country’s largest steel producer. RECSA-LOTA was positioned to penetrate the Southern Cone Common Market, particularly in the copper industry markets. Harbison continued to evaluate potential regional opportunities in response to the Latin American growth and industry privatizations.

Harbison revenues hit an all-time high in 1997, reaching $333.5 million with an increase of 12 percent over the previous year. A large-scale cost reduction program had been initiated domestically and was partly accountable for profit increases. The cement business had also improved as a result of a strong U.S. economy and mild weather in the North for the year. Harbison’s response to the decline in the availability of skilled bricklayers, which was driving up costs, involved a plan to move customers to monolithics (a furnace lining without joints), which were cheaper to install because they were less labor-intensive and required reduced furnace downtime. Looking ahead, the company planned to distance itself from the strong competition by moving away from being “only a product supplier to being a solution supplier,” according to company statements. Plans were focused not only on providing refractory products but extended to include the removal of old and the installation of new products as well.

Below – This similar brick was found at the same location by Ian Suddaby. It is believed to be stamped HW 3.