Kilchattan Brick and Tile Works, Kingarth, Isle of Bute – sometimes Kilcattan.

Kilchattan Brick and Tile Works – By T. Gilmour – (published 1949) – Source

My only experience as a practical tilemaker is being taken over to the works as a child of 5 by my grandfather to see the last kiln being burned. That was in the year 1915. In my researches, however, I have been exceedingly fortunate in obtaining first-hand information from one of the last of the old tilework’s men, Mr Hugh Gill, who now was an octogenarian, commenced work in the tilework’s as long ago as 1883 when a boy of only 13 and worked there until production ceased in 1915. Mr Gill’s father served in the works from the time when my grandfather took over the tenancy in 1866, so that I have had the benefit of as good as first-hand information for all but the first 17 years of the tilework’s existence.

As far as I know, Kilchattan Tileworks were built fully 100 years ago. The date on the porch of my house is 1849 and I understand that the works were built a few years before the house. The tileworks were built on the initiative of a former Marquess of Bute and in addition to making bricks and tiles, they also served as the Estate Sawmill. The original tenant had the rather imposing designation of “Master of the Tilework” but in spite of this impressive title he and his successors were not too successful in business. By the year 1855, the tileworks were idle. My authority for this fact is an old Tourist Guide to the Clyde which I saw a few years ago at a Clyde Steamer Exhibition in the Mitchell Library. It stated that “At Kilchattan there is an extensive tilework, at present unhappily idle due to competition from the Ayrshire works” The tenant immediately before my grandfather was a man named Thomas Todd. He was no more successful than his predecessors and my grandfather, who was not a tolerant man, attributed his non-success to the fact that “Tam Todd wore a white sark to his work.”

The forerunner of the tile drain was the stone drain and a laborious job it must have been collecting suitable stones and laying them. This method of draining was used during the latter half of the 18th century. It was not until the 19th century that a burned tile was used. The first type of tile produced was what is known locally as a “mug” tile. It was rather a crude product, made by hand. My grandfather never made “mug” tiles.

At the time my grandfather took over the tenancy the tiles were still made by hand but within a few years, besides introducing his own patented design of power-driven tile machine, he built a second kiln, extended the drying capacity of the works and built a steam-heated brick-drying stove. The reason for this activity was the introduction of government-assisted draining. This was a very enlightened policy and hundreds of thousands of acres of land were tile-drained and brought to a high level of productivity. The Marquess of Bute took full advantage of the government grants and for some thirty years, a minimum of 256,000 tiles per annum were buried in Bute. Normal annual production was about 1 ¼ million tiles and half a million bricks so that the bulk of the production of tiles had to be exported. Over the years a very extensive trade was built up throughout the Western Highlands and Islands and also in Northern Ireland. Many tales could be told of the men and boats engaged in this trade. Kilchattan was quite a port. My grandfather had his own boat, an old jigger, the “Christina and Janet” of 70 tons burthen and in addition there were the locally owned smacks “Duchess,” a product of Ardmaleish Yard and a flyer in her day, the “Cottage Girl” and one or two smaller vessels of 25/30 tons burthen. Those boats were engaged mainly in the tile trade, carrying dross from Ardrossan for burning the kilns, tiles to Campbeltown, bricks to Tarbert, tiles to Islay, to Tiree and as far north as Stornoway. Kilchattan tiles were famous and there is nothing approaching them in quality being made today. Only a few days ago I was telephoning a Department of Agriculture official to see if he could give me any ideas of the number of tiles that would be required in Bute over the next few months, but in spite of the fact that quite a few schemes were going on it was mostly a case of lift and relay, as the Department considers that it is better to relay Kilchattan tiles, although it is 40 years since they were last made.

At this point, I might give you a rough idea of the layout of the tileworks. The nerve centre was the engine house and milling plant. Attached to the engine house was another building that housed the smithy, workshop and stores. The prime mover was a very ancient steam engine supplied with steam from a 25’ x 3’ egg-ended boiler. In addition to providing steam for the engine, the boiler also supplied the steam for the brick-drying stove. Factory regulations were pretty lax in those days. When an extra head of steam was required, the simple but effective method was used, of tying down the weight that operated the safety valve. But there was never a serious accident during the whole history of the works and the old engine that had come from a pithead in Ayrshire back in the forties of last century provided the power until the works closed. Incidentally, there was a huge flywheel, which still lies where it was dropped when the machinery was scrapped in 1935 and according to local tradition this flywheel came out of a Rothesay Cotton Mill. I cannot vouch for the truth of this. Another building housed the clay cutters, rollers and the pulleys which operated the tile machines by means of endless ropes. Radiating from the Mill Building were the two large drying sheds, each had some 120 feet long. Those sheds had a drying capacity of some 50,000 of 3’ tiles and in their day were the biggest in Scotland. Tile making was never what one might call “big business” and most of the works were managed by the owner or tenant with a staff of some 20 men. The kilns were massive affairs; one of them exists until this day, having been converted to a very useful shed. Each kiln, which was of the updraught type, had a capacity of about 60 tons of tiles. The kiln was fired through 26 fire holes, 13 on each side of the kiln, and it took some 30 tons of dross to fire one kiln.

In its heyday, the tilework employed some 20 men. In addition to the direct employees, it provided the bulk of the work for the locally owned smacks and also was the main source of livelihood of half a dozen carting contractors, who were engaged in carting dross from the Old Quay and tiles back. When draining was at its peak in the eighties of last century there was tremendous competition among the farmers to get tiles and it was not unknown for carts to start off from the North End of the island shortly after midnight to get a place in the queue for the kiln being emptied in the morning. In the early days of this century, there were no telephones available, but there was a telegraphic service from Kilchattan Bay Post Office. In connection with the shipping side of the business, there was a constant receiving and sending of telegrams. When my grandfather had to send a telegram he simply wrote on a tile and gave it to a carter to hand it into the Post Office. The tile was put under the Post Office counter to be kept as a record and periodically an S.O.S. would come from the postmistress to send a cart to collect the old telegrams!

The reason for the decline and ultimate closing down of what was at one time a flourishing industry was really a lack of demand. For a few years, my grandfather had a taste of what his predecessors had feared and nothing could be done about it. After the turn of the century, it became more and more difficult to find a market for the output. Bute could absorb only a fraction of its former requirements and the market was latterly limited to Campbeltown district and an occasional cargo to Islay. Combined with the decline in demand was the fact that the original clay bed had become exhausted and the new pit, which was opened in 1908, was a pit in all conscience. Eighteen feet of subsoil and sand had to be bared before the clay was reached. Even today this would be quite a task, but back in those days of pick and shovel, it was hopeless from the start. Nevertheless, the pit was opened up, a pumping plant installed to keep down the water level and the business struggled on until 1915 when the last kiln was burned. My grandfather had kept the works on a care and maintenance basis for many years but agriculture remained in the doldrums and the works never re-started. As you all know, in the uneasy years between the wars no money was available for capital improvements such as land drainage. When the Second World War broke out in 1939 most of the smaller works had gone out of existence and the few works left could not cope with the demand that arose for the tiles. I am often asked if it is not possible to restart the industry. Apart from the very considerable capital outlay that would be involved, it is doubtful if the local market would absorb even 10 per cent of an annual output of say 1,000,000 tiles. It never was possible to compete on the mainland of Scotland apart from the extreme West, so that the market would be limited to the Western Highlands and Islands and demand there is very problematical. In regard to bricks, the very quality of porosity that made such a good tile made a rather indifferent brick except for partition work, so that in my opinion the re-starting of the industry is not a practical proposition.

Although tiles are not made now, the old works are still in use and it says much for the materials and workmanship of more than a hundred years ago that the original drying shed still stands, having withstood a century’s gales, and the original yellow pine drying racks are still in daily use for drying poultry shell and grit.

Footnote: Mr Gilmour adds: I learned recently that the present Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia is the grandson of the Tam Todd mentioned above. The P.M.’s father was born in the house in which I now live. The family emigrated to New Zealand in 1864, where they amassed a fortune making – bricks!

***********************

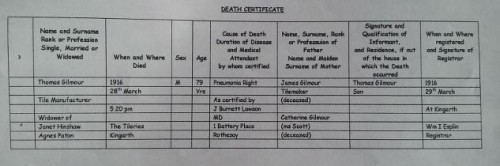

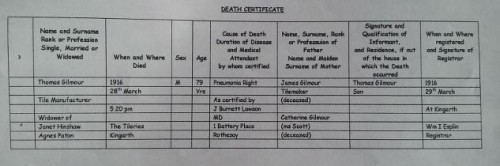

Thomas Gilmour was a manager at the Kilchattan Tileworks. This entry shows in was Manager in 1903. He died in 1916.

The shell-bearing clay at Kilchattan Tileworks, Bute is described as – The deposit lies at the northwest side of Kilchattan Bay, beyond tide-mark, and slips seaward. Taking the beds in descending order, we find –

I. – Peaty mould: about 1 foot.

II. – Gravel : 3 to 5 feet.

III. – Muddy sand: 4 to 6 feet.

IV. – Grey laminated clay: 6 to 7 feet.

V. – Reddish boulder clay: depth unknown.

At Kilchattan Tileworks, Buteshire, the fossils of all species are most plentiful, above the laminated clay, in a bed of sand or gravelly sand, which lies between the clays and the upper gravel.

More info on the clay beds can be found at Canmore

Scottish Places

All that is now readily visible of Kilchattan brick and tile works (1885-1915)? is a building that formed the apex at the N end of two long ranges, which has been incorporated into a modern kitchen garden. The building, which may have been a smith’s workshop (see MS/500/43/2), measures 6.7m from N to S by 5.4m transversely within coursed, mortared rubble walls that stand up to 3m in height. There is an entrance and flanking windows in the W side and in the N end there is a blocked window and a vertical flue. The S end-wall is missing and the interior of the building now contains a series of raised vegetable beds. A kiln, which is depicted on the 1st edition of the Ordnance Survey 6-inch map (Buteshire 1869, sheet CCXV) standing immediately SSE of this building, has been reduced to a large mound of rubble.

Visited by RCAHMS (AGCH) 19 May 2009.

The following photographs plus others, plus further info can be reached at this Canmore link.

The following link from ‘Scotland Places‘ supplies some fascinating information and photographs of the brickworks. The manuscripts section details some very interesting articles which I must try and lay my hands on at some point. If anyone has access to any of these documents I would love to see the content.

The following 2 photographs are of bricks found on Kilchattan Bay, very near to the brickworks. They are believed to have been the type made at the works. Their proximity to the works, the colour of the clay and the fact they appear to be shell bearing, all point to these being original Kilchattan bricks. These were kindly photographed on Bute by Tom Cromack.

.

Below – A magnificent example – T Gilmour, Kilchattan photographed at the National Museum Scotland collection centre, Edinburgh. (Note – SBH – I do not have an example of this brick so if anyone trips over one ….!)

13/11/1849 – Greenock Advertiser – Marriages – At Braeside Cottage, Rothesay on the 6th, by the Rev Thomas Neilson, Mr Thomas Todd of Kilchattan Tileworks to Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Mr Robert Wright, Merchant, Rothesay.

04/04/1851 – Glasgow Herald – Notice to creditors – Thomas Todd, brick and tile maker at Kilchattan, Island of Bute, having executed a disposition omnium bonorum, of the whole effects in favour of Hugh Allison, Coal Merchant, Glasgow for behoof of his creditors, all parties having claims against the said Thomas Todd are requested to lodge same with Wylie and Mitchell, Accountants, 100 St Vincent Street, Glasgow before 20th April.

25/05/1853 – Dundee Courier – Sequestrations – Adam Brown Todd, brick and tile manufacturer, Kilchattan, County of Bute and at Wellhill in the Parish of New Cumnock and County of Ayr.

24/02/1864 – North British Agriculturist – Creditors of Adam Brown Todd, brick and tile manufacturers at Kilchattan, county of Bute, and at Wellhill, in the parish of New Cumnock, and county of Ayr, meet in the office of Thomson & Craig. accountants. 70 George Square, Glasgow, on Wednesday, 9th March, at 12 o’clock. Robert Craig, trustee.

1855 – 1864 – ScotlandsPlaces – Kilcattan Tileworks. Mr Reid occupier. A modern building erected by the Marquis of Bute for the accommodation of his tenantry. These works are locally termed “Kilcattan Tile Works”

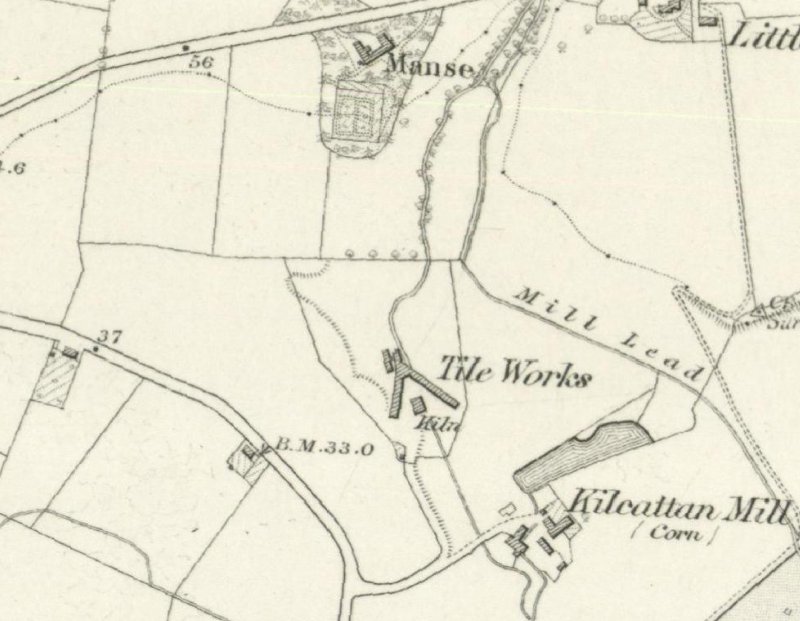

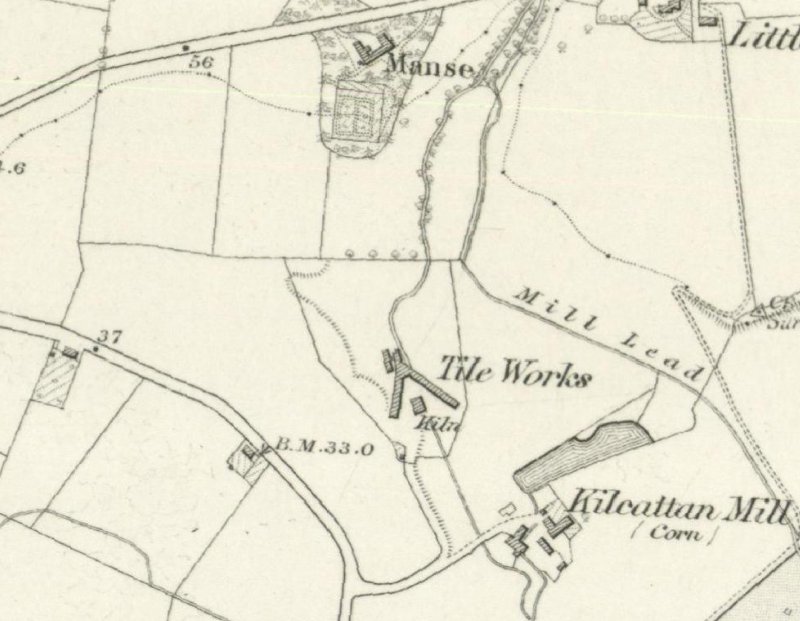

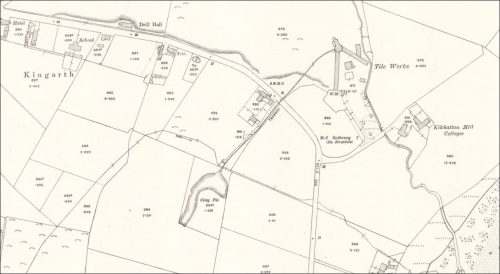

Below – 1863 – Kilchattan Tileworks, Isle of Bute.

Below – 17/10/1865 – Glasgow Herald – Tileworks and sawmill, farms and lime works on the Bute Estate to let.

11/12/1869 – Oban Times – Thomas Gilmour, drain and tile manufacturer, Kilcattan Tilework by Rothesay, Bute has on hand a large stock of drain pipes from 2″ up to 3″. Prices of the various sizes put on board at Kilcattan Bay sent on application. Kilcattan Tilework by Rothesay, Bute. 02/10/1869.

25/03/1876 – Rothesay Chronicle – To the electors of the Parish of Kingarth. Having been nominated candidate for the School Board, should you think it to elect me. I will endeavour to the best of my ability to assist in carrying the education in an efficient manner in the different districts of the Parish. Thomas Gilmour. Kilcattan Tile Work, 24th March 1876.

23/08/1876 – North British Daily Mail – Portable engine and threshing machine by Clayton and Shuttleworth. Good order. Apply Thomas Gilmour, Kilchattan Tileworks, Rothesay.

03/11/1877 – Rothesay Chronicle – The subscriber has for sale a quantity of clean white sand suitable for plasterers. Can be sent to Rothesay by boat. Thomas Gilmour, Kilchattan Tilework.

10/11/1877 – Rothesay Chronicle – Wanted, a man to take charge of a sailing smack. Apply to Thomas Gilmour, Kilchattan Tileworks.

1886 – Thomas Gilmour, brick and tile manufacturer, Kilchattan Bay, Rothesay p.356

Below- 27/09/1886 – Glasgow Herald – From Uddingston, we learn that a company landed at the quarry and were overcome by gaseous vapours – The son of Mr Thomas Gilmour, Kilchattan Tileworks, who was injured at Crarae on Saturday is recovering but he is still confined to bed in Mackinlay’s Temperance Hotel, Rothesay.

14/05/1887 – Rothesay Chronicle – Wanted. Offers for freight of coals from Ayr to Kilchattan. Apply to Thomas Gilmour, Kilchattan Tileworks.

25/03/1893 – Glasgow Herald – Draining pipes for sale at Kilchattan Tileworks, Bute.

1896 – Thomas Gilmour Kilchattan Bay.

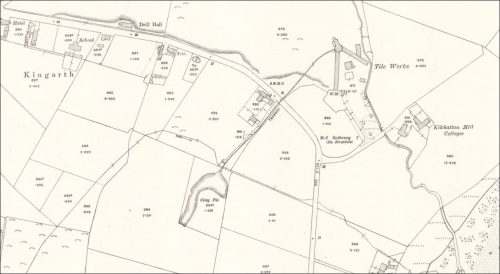

Below – 1896 – Kilchattan Tileworks, Isle of Bute.

1899 – 1900 – Thos Gilmour, Brickmaker, Drumchapel Brickworks, Drumchapel, Bearsden, Glasgow.

1901 – Directory of clay workers – Thomas Gilmour, Kilchattan Bay, Rothesay, Buteshire.

1903 – T. Gilmour, Kilchattan Bay, Rothesay.

Below – 1915 – Kilchattan Tileworks, Isle of Bute.

Below – 28/03/1916 – Thomas Gilmour, Kilchattan Tileworks died.

14/04/1916 – Linlithgowshire Gazette – The late Mr Thos Gilmour. A native of Linlithgow Bridge. Related to Henry Bell of ‘Comet’ fame. A well-known Bute personality Mr Thomas Gilmour of Kilchattan Tileworks has just passed away in his 80th year and it is interesting to recall that he was a native Linlithgow Bridge and a relative of Henry Bell of ‘Comet’ fame. He was brought up in the joiner trade, and in his youth worked in the Caledonian Railway Workshops in Glasgow. After that, he managed a fire brick and tile works, and for time he was in partnership with a brother in an engineering shop in Glasgow, under the name of Gilmour and Co. He subsequently took the Kilchattan Tileworks and in November last completed fifty years’ tenancy of the place, being, it is believed, the oldest tenant on the Bute Estate …

1923 – Thos Gilmour, Tile Manufacturer, Kilchattan Bay, Kingarth, Bute.

30/11/1937 – The Scotsman – Reference to Dugald McIntyre, Millhouse, Kilchattan Bay, Bute and his wife celebrating their diamond wedding. They married 60 years ago and Mr McIntyre was formerly the leading hand at Kilchattan Bay Tileworks.

Gilmours – Brickworks, Essenside Drive, Old Drumchapel, Glasgow.

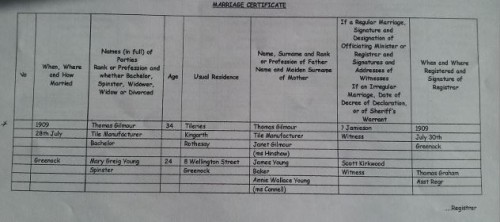

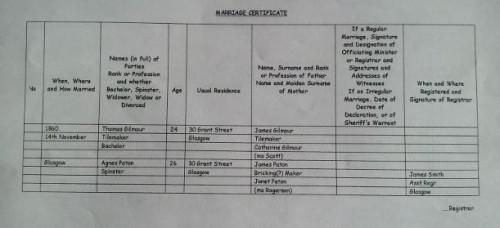

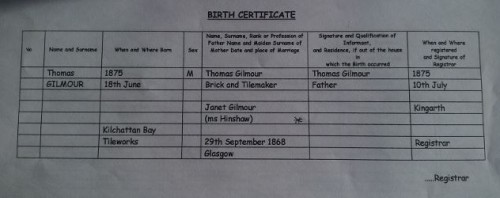

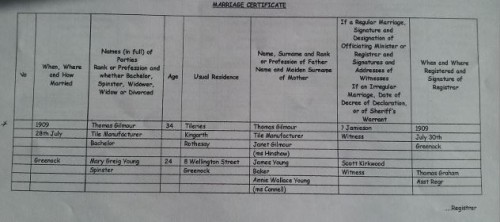

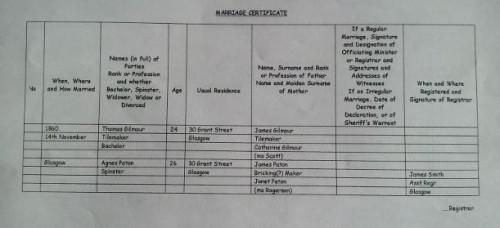

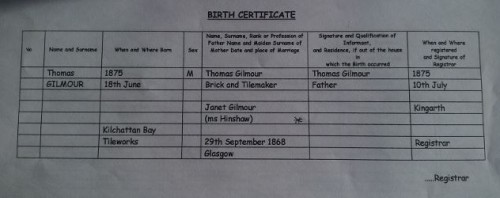

Below – Some copies of registrar extracts relating to the Gilmour family – many thanks to Eric Flack for this information.

.

Below – The Thomas Gilmour referred to in the extract below as being married on 28/07/1909 ran the brickworks in Drumchapel, Glasgow