08/12/1840 – Liverpool Standard – On an improved method of constructing and stoking the furnaces of tile kilns. (By Mr James Taylor, Moorfield Tileworks, Kilmarnock, actor to the Duke of Portland.) Mr Taylor’s original paper on the manufacturing of drain tiles (for which the society’s gold medal was awarded) will be found in vol. xii. p. 27, of the Transactions, and to which the following communication forms an addendum. The increasing demand for drain-tiles, and consequent competition in its manufacture, has stimulated those engaged in it to arrive at the utmost economy in the cost of construction and it having been assumed that the construction of furnaces would materially affect the expense in the article of fuel, much inquiry has been set on foot, and expensive experiments conducted, with a view to ascertain the best method of applying this expensive agent. Hitherto, it is believed, reduction in the expense of fuel has been but partially successful. A communication, therefore, on this point, coming from a person of experience and giving his own actual experience of the improvement, will, no doubt, be duly appreciated.

Mr Taylor’s communication is expressed in the following terms. The following brief description of my economical method of burning tiles and the advantage of it compared with the methods generally adopted in this part of the country, may not be unwelcome. The main point of this method consists in adapting the furnaces of the kiln to produce a greater effect from a given quantity of fuel than by the old system, but I have also found that a large portion of the fuel may consist of refuse of coal, or as it is commonly called ‘coom’. To effect this end, grate or furnace bars of the form usually adopted in engine and other furnaces are fitted into the fireplaces of the kiln, which are further assimilated to ordinary furnaces by being fitted with closing doors. The height of the ashpit, or space between the floor of the stoking vault, and the furnace door-sole I make 15 inches, and its width 12 inches. The door-frame, which may be set about 6 inches square, through which the fuel is thrown into the furnace. The two sleepers, which support the bars, are each 18 inches in length, to allow their ends being fixed in the walls, and are placed the first at the distance of six inches, the other at twenty-four inches from the door-frame; on these sleepers are laid seven furnace-bars of eighteen inches in length, a dumb plate of six inches in breadth, filling up the space between the ends of the bars and the door-frame. Beyond the grates thus formed, there is a space of one foot of dumb wall, and in this space the furnaces are contracted uniformly in width to nine inches at their entrance into the kiln, while their height is uniformly augmented from the door inward, till, at the entrance to the kiln, they are twenty-six inches in height, and their sole one foot above the level of the inside floor. Fireplaces of the above description, when culm is used for fuel, are more powerful, and the temperature more easily regulated, than in those where the fires are placed on the ground, and allowed to choke up till the fireplaces are full. The furnaces are cleared two or three times during the process of burning; and as none of the fuel is allowed to go into the inside of the kiln, there is less risk of the tiles being vitrified and twisted than in the common form, where the burning fuel frequently comes in contact with the tiles lying near the entrance of the fireplaces.

It is of great importance in burning tiles, that the heat should ascend regularly through the whole kiln, and tile burners have experienced much difficulty in regulating this point. One or two of the fires may sometimes burn slowly, while those on either side of them may burn freely. If this evil is not wholly obviated by using the grate, the remedy is at least rendered easy of application; for, by opening one inch more or less of the doors on each side of the dull fires, the draft is considerably increased in them, and their action is equalized to that of the others. Should the temperature appear to be too high in any of the furnaces, the doors of those have only to be opened a small space, which will check the increase of heat. In this way, the door of each furnace can be made to act as a regulator for its own fire, as well as to act upon those immediately adjoining.

The coal required to burn a kiln containing twenty-five thousand tiles, constructed on the old plan, cost, at the pit, £3 12s. The quantity of fuel that I require to burn the same kiln, by the new method, and its cost at the pit, are,

2 1-10th tons coal, at 5s 10d per ton … £0 12 3

10 tons of culm, at 1s 3 per ton … £0 12 6

being a saving of £2 7s 3d on the burning of a kiln, or nearly two shillings per thousand tiles. Quarterly Journal of Agriculture for June, 1839.

05/06/1841 – Northern Whig – Ayrshire Agricultural Associations Annual Exhibition … No agricultural implements were shown and only one model of an improved tile kiln by Mr James Taylor, Moorfield Tileworks, Kilmarnock.

31/01/1849 – North British Agriculturist – There is no branch of husbandry which has undergone such a wonderful change, and at the same time been subject to so much diversity of opinion as to the method of draining the superfluous moisture from the land in Ayrshire. A few particulars narrating the different modes practised may be interesting at the present time. When the Duke of Portland introduced the manufacture of tiles into this county, with the intention of supplying a useful and permanent material, whereby the drainage of his estates might be thoroughly effected, the innovation was looked upon by his numerous tenantry and many of the surrounding proprietors as a mere whim of his Grace. Only two out of the whole tenantry, could at their first introduction be induced even to make a trial of the tiles, and they too, I am told, entered upon the experiment in a very apathetic manner.

In a few years, however, such was the visible improvement this process bad in ameliorating the soil, that the whole tenantry became desirous to adopt the same method. In awarding the meed of praise to the Duke of Portland, as being the first to introduce tile draining into this county, for the benefit of his tenantry, I consider that the name of the person, who first attempted the manufacture of the tiles, should also be recorded. This was Mr John Morton, Kilmarnock, (lately deceased) an individual well known for many years as a worthy member of our horticultural societies. So far back as the year 1821, Mr Morton was applied to by the Duke of Portland to make tiles for him. Mr Morton was at that time carrying on a brickwork at Croftfoot, near Kilmarnock. (Does anyone know the exact location of these works?). The Duke furnished him with two wooden patterns and also sent a tile from England, which was denominated a 7-inch tile and had flanges to rest on instead of soles, which flanges were about two inches broad. Mr Morton made a few hundreds that year (1821) and burned them amongst the bricks. The next season he made the above-named size, and a size larger, but had no erections exclusively for tiles, the number wanted not warranting the expense. Mr Morton also made some tiles for Mr Guthrie of Mount, and others.

In 1823 the Duke sent a man named Robert Busbie to make tiles on a larger scale, who erected his work at Westmuir, on the side of the Troon Railway, near Kilmarnock, who made tiles for two years.

The Duke, being fully aware of the advantages of tile draining, and now seeing that his tenantry were beginning to appreciate such, resolved to erect works on a still more .extensive scale, sent down two persons from England to carry his plans into execution, namely Mr Cresswell, and Mr Tibet; the former being acquainted with the manufacture of tiles, and the latter with cutting the drains, and laying them down properly. After looking over the different fields of clay, that of Moorfield was fixed upon; Mr Cressewell undertaking the charge of erecting the works there, necessary for their manufacture. Mr Cresswell continued to carry on the works at Moorfield for three years with great success, he being a very expert workman, thoroughly understanding tile making in all its departments. At the end of the three years, Mr Cresswell left Moorfield and went back to England, leaving the works there all in complete order. Mr Thomas Wilson then undertook the management of the Moorneld works till the commencement of the year 1829, at which period Mr James Taylor was sent from Staffordshire, who still continues successfully to carry on the manufacture of tiles at that establishment.

In thus giving a few brief details of the rise and progress of tile making in this county, there is one individual who justly deserves to be mentioned as having laboured with great success, and to whose exertions the Duke of Portland’s works are also much indebted. The individual I allude to is, Mr William Freborough, who first came from England with Mr Cresswell to Moorfield and continued there for a length of time after Mr Cresswell went to England. Mr Freborough subsequently burned tiles in different parts of Ayrshire, and is now, I believe, in Fifeshire.

When tile draining came to be generally appreciated by the Duke of Portland’s tenantry, a systematic arrangement was instituted, whereby the depth of the drains was regulated, and the distance apart, and a stipulation as to the percentage exigible for each acre so drained. Eighteen inches was then the maximum depth, and eighteen feet the minimum distance asunder of the furrow drains, which arrangement was rigidly adhered to, whatever might be the nature of the subsoil, or the inclination of the field to be drained

However indifferent our modern drainers may look upon such a system as that which was adopted at the outset, the effect produced therefrom was such as to warrant an extension of that very system.

Sir James Graham of Netherby Hall was one amongst the many who strictly adhered to the Duke of Portlands 18 inch system, and it was only when he had a great part of his estate drained that Sir James discovered an imperfection in the mode he had been pursuing. At a dinner which was given by the Highland and Agricultural Society, at the close of their meeting in the year 1838, Sir James, whilst recounting the many advantages derived from tile draining, at the same time regretted very much that he had not cut the drains considerably deeper, more especially as he was now prevented from using with advantage Mr Smith of Deanston subsoil plough.

The late John Hamilton of Sundrum may be justly styled the father of furrow draining in this county, inasmuch as he drained extensively with stones long before tiles were introduced. In the year 1834, when other proprietors were implicitly following in the wake of the Duke of Portland, Mr Hamilton, with his well-known discernment advanced considerably ahead, and substituted a new system, which was still. only the precursor of greater innovations. In that year 1834 Mr Hamilton drained on the Sundrum estate fifty acres with tiles, and in order to show the superiority of his system, a specification of how one of his fields was accomplished may be interesting, and may still serve as a model to some of our modern drainers.

The park to be drained in every furrow, the ridges being 12 feet broad, and 22 inches deep. The earth must be all carefully laid to one side, and the bad earth to be scattered over the ridge; the drains to be made smooth at the bottom dad with a proper declivity. Where soles are required, the drain to be rounded to answer the bend of the sole; two falls to be soled at the bottom of every furrow drain; the one fall next the main drain to be done with good soles, the other to be done with pieces laid close together and carefully jointed; the tiles to be laid in a straight line, and put so as not to remove out of their places; the tiles to be covered with straw, to be packed over them carefully, and the thickness to be regulated by the proprietor or those whom he may appoint; then the good earth to be put in next the straw in a careful manner, not to displace the tiles; whatever more is required to fill the drains to be taken off the edges in a slanting direction, and the whole filled smoothly.

The main drains to be four inches deeper than the furrow drains, and to be laid all with soles, and to be laid in the same careful manner as specified in the furrow drains.

Where the furrow drains run into the main drain an opening is to be left, and that opening to be carefully laid over with pieces of tile; the bottom fall of the furrow drains to be gradually sloped down to where it discharges itself; to have only one inch of a drop; the sole of the furrow drain to overlap the sole of the main drain; where any inequality of the ground may happen to intervene, it must be cut through so as to preserve a proper declivity.

All the above-mentioned to be done to the satisfaction of the proprietor, and finished by the latter end of December.

October 1, 1834. (Note – SBH – Could this John Morton be the father of the John Morton that would later become associated with the Bonnyton Fire Clay Works?)

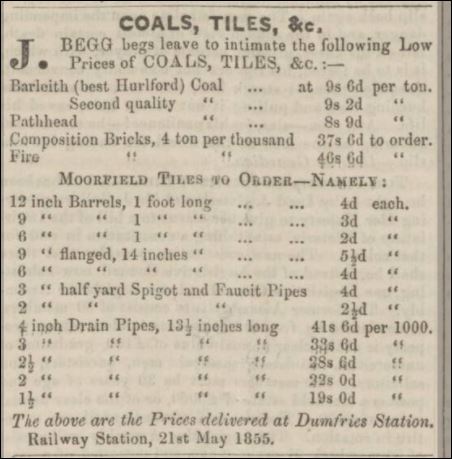

Below – 23/05/1849 – North British Agriculturist – Price list for Moorfield Tileworks.

Below – 18/04/1850 – North British Agriculturist – Price list for Moorfield Tileworks., with reference to Gargieston Tileworks.

1851 – 1852 – James Taylor, tilemaker, Moorfield Tileworks, Kilmaurs, Ayrshire.

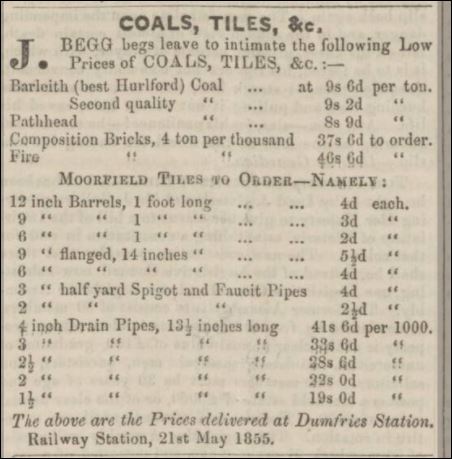

Below – 06/06/1855 – Dumfries and Galloway Standard – J Begg stocking Moorfield Tiles.

Below – 1856 – Moorfield Tileworks, Coalhill.

21/02/1856 – Stirling Observer – The late storm – Kilmarnock. The most painful disaster during the late storm was occasioned by the fall of a large brick stalk at a coal pit, on the lands of Skerrington, belonging to Messrs A. Gilmour & Co … The stalk was considered quite firm and was built of the best Moorfield brick.

1862 – Moorfield Tileworks. J. S. Taylor, Kilmarnock.

07/10/1864 – Edinburgh Gazette – Trustees acting under the Deed of Settlement of the late James Taylor, Tilemaker at Moorfield, in the Parish of Kilmaurs, ceased, as from the 31st day of December 1863, to have any concern in the carrying on of the deceased’s Brick and Tile Works at Gargieston and Galston, which, from and after that date, have been, and now are carried on by the Subscriber, James Smith Taylor, on his own account. John Sturrock, Agent for Jas. Taylor’s Trustees.

1868 – … brick and tile making have long been carried on at Moorfield by Mr Taylor’s family …

1868 – Moorfield Brick and Tile Works, Kilmarnock. William P Robertson, manager, Gargieston Cottage, Kilmarnock.

1872 – W. P. Robertson, Moorfield Tileworks, Gatehead, Kilmarnock. House, Gargieston Cottage.

1872 – William Taylor and Co, fire clay manufacturer, Moorfield by Kilmarnock. Place of business The Angel Inn every Friday.

21/10/1874 – Invoice – Moorfield Pipe Tile and Brickworks. William Taylor and Co.

04/08/1881 – Ayr Advertiser – Deaths. At Moorfield Tileworks, Kilmarnock on 3rd August. W. J. Robertson in his 61st year. Friends, please accept this invitation.