Shawsrigg Fireclay and Enamelling Company, Larkhall, North Lanarkshire.

See also

Southhook Fireclay Works, Dreghorn, Kilmarnock, East Ayrshire.

See also

Bonnyton Fire Clay Works, Kilmarnock, East Ayrshire.

Shawsrigg or Shawrigg.

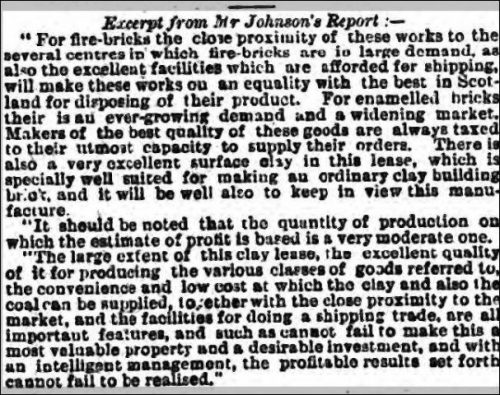

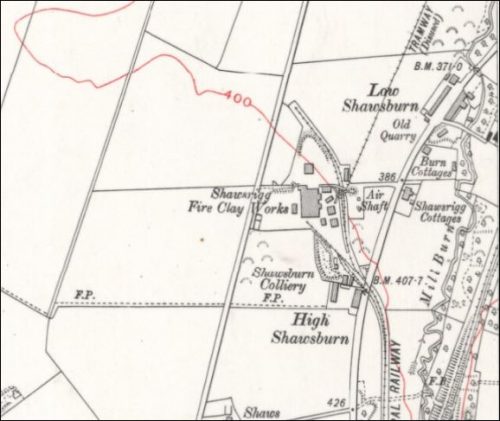

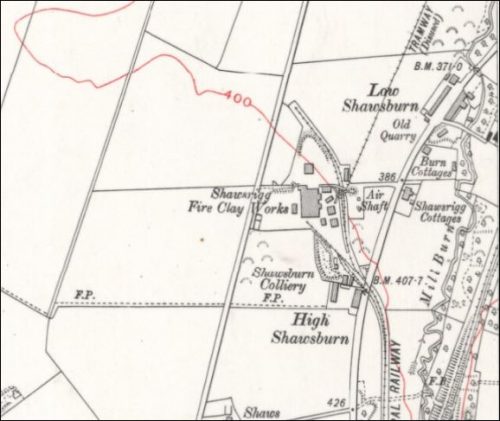

Shawrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co., Ltd – The company was incorporated in 1895 to continue the business carried on by William Hunter at Jamaica Street, Glasgow and at Larkhall. Hunter had taken over an earlier business, the West of Scotland Fireclay and Sanitary Enamelling Company Limited. He took a lease from Henry Hamilton of Raploch dated 1895 covering 200 acres in the lands of Shawburn and Harelees. Their brickworks was situated about 1 1/2 miles southeast of Larkhall, near Shawburn Colliery and was connected to the Shawrigg pit by a mineral railway. The Company went into voluntary liquidation in 1910, when its assets were bought by the Southhook Fireclay Company. It continued trading as Southhook and Shawrigg Fireclay Co Ltd at least to 1921. – Source Kenneth W Sanderson.

1895 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co. Ltd Registered.

03/09/1895 – Glasgow Evening Post – New company – Shawsrigg Fireclay and Enamelling Company. Incorporated to carry on the business of William Hunter, Shawsrigg, Colliery.

.

.

.

.

Below – 1896 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay Works.

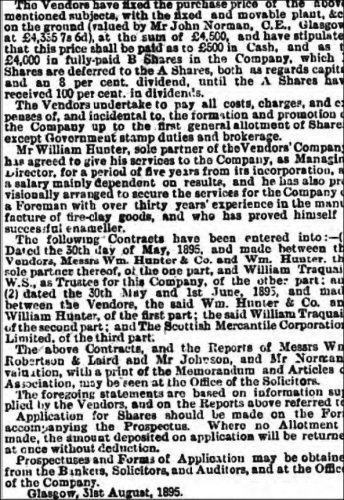

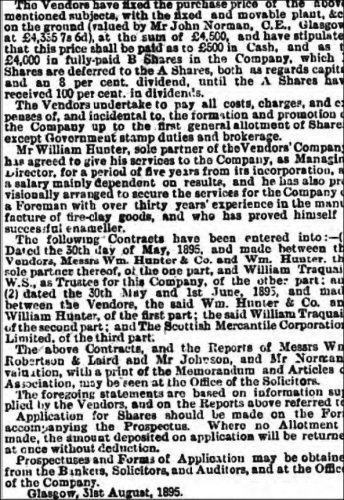

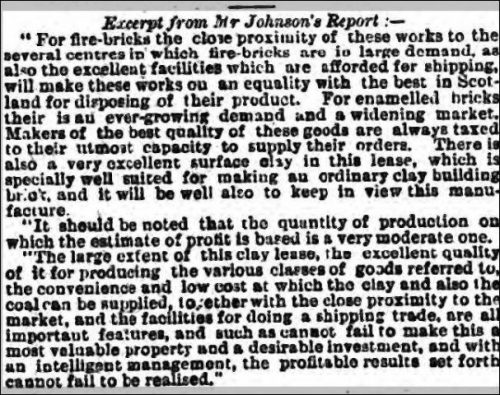

14/09/1895 – Glasgow Herald – New joint-stock Scottish company. The Shawsrigg Fireclay and Enamelling Company, formed with a capital of £15,000 divided into shares of £1 each to acquire and carry on the business of coal masters and manufacturers of bricks and fireclay goods presently carried on by Messrs William Hunter & Co, 49 Jamaica Street, Glasgow and Shawsrigg near Larkhall. The registered office is 49 Jamaica Street, Glasgow. The first subscribers were:- Alex Muir, builder, 400 Eglinton Street; Andrew Gray, wright and builder, 30 Bath Street; William Hunter, coal master, 49 Jamaica Street; Alex Morrison, merchant, Bearsden; David Stirling, colliery agent, 49 Jamaica Street; John H. Martin, bookkeeper; W. Traquair, W.S., 11 Hill Street, Edinburgh.

31/07/1896 – Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald – Fire clay workers wanted. Experienced in kiln building. Permanent job to a suitable party. Kiln setter, with experience in setting enamelled bricks. Enamelled brick dipper, experienced. Apply, Shawsrigg Fireclay Co Ltd, 49 Jamaica Street, Glasgow.

12/09/1896 – Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser – New industry – The Shawsrigg Fireclay and Enamelling Company, by the cutting of the first sod of which ten months ago a new industry was opened up in the Larkhall District of Lanarkshire, are now is almost full operation, and on Friday, on the invitation of the directors, a party of about sixty gentlemen, chiefly shareholders. travelled from Glasgow for the purpose of inspecting them. The party left the Central Station by the one o’clock train for Ayr Road, and upon arriving there brakes were taken for the works. A complete tour was made through the various departments in connection with these, and all the processes in the making of fireclay bricks, enamelled bricks, and other enamelled ware were witnessed, from the raising of the rough, formless clay out of the pit to the turning out of the finished article. Thereafter the party drove to the Commercial Hotel, Hamilton, where luncheon was served, Mr John Paterson, chairman of the directors, presided, and amongst those present were Colonel Bennett, Mr William Hunter, Mr Alexander Muir, Mr Andrew Gray, Captain Paterson, Glasgow; Mr White, Glasgow; Mr Melville, and others. Several toasts were proposed, the most important being “The Shawsrigg Company,” and the chairman was presented with a silver drinking cup by the directors as a mark of their esteem. After the luncheon, the train was again taken from Hamilton to Glasgow, the party arriving in the western capital shortly after six o’clock.

17/11/1897 – Glasgow Herald – The second annual general meeting of the Shawrigg Fire-Clay and Enamelling Company (Limited) was held yesterday in the office of the Building Trades Exchange, Gordon Street. Mr John Paterson presiding. The annual report for the year ending 31st August stated that during the year additions were made to the drying room accommodation and to the kiln buildings at Shawsrigg Works and the cost of these had been charged to capital. The upkeep and maintenance of buildings and plant had been debited to revenue, and the works were at present in excellent condition. The greater part of the profit for the past year had been earned during the last four or five months of the year, as prior to that time the works could not be put into full operation, owing to the additions above referred to not being completed till the month of May. In the earlier months, the directors had also to meet the difficulties experienced in introducing a new article upon the market and for a considerable period, the sales made were less than the output. Gratifying progress had now been made in this respect, and the deliveries for several months had exceeded the production, while the order book shows that she works would be fully taxed for months to come to meet orders presently in hand. The sum at the credit of profit and loss account was £1049 9s 7d. The directors recommended that a dividend of 5 per cent. be declared for the past year on the A shares of the company, absorbing £559 9s 3d of this sum; that £83 9s 3d be applied to write down the preliminary and legal charges account and that the balance of £40617s 3d is carried to the suspense account to meet contingencies. Since the close of the financial year, the board had arranged to build a few houses at Shawsrigg on a feu which had been taken off near the works to provide accommodation for the works’ manager and others. The estimated cost of these houses was under £400. Owing to the need for holding a large stock of enamelled goods at the works to meet the requirements of the trade the working capital of the company had been found too small, and the directors arranged for an overdraft from the Bank of Scotland on their personal guarantee. They had also considered the question of increasing the capital of the company to provide for present wants in conjunction with the question of an enlargement of the works and recommended that the board to be elected at this meeting should at once proceed with a moderate extension and arrange for a further overdraft to cover the cost meantime. Also that the company’s books should be balanced at the 28th February next, and the profits on the current half-year’s working ascertained and that a carefully prepared scheme for the enlargement or reconstruction of the company should be laid before the shareholders as soon as possible after that date. In connection with this scheme, the directors advise that it should provide for an increase of capital sufficient to double the output of enamelled goods and to, take up the manufacture of sewerage pipes, vitrified bricks, terra cotta goods, and common building bricks, for all of which there are suitable materials in the company’s property. The Chairman, in moving the adoption of the report and statement of accounts, said that all parts of the works were now in proper order and the sales were going on steadily. During the past two months, things had been very satisfactory, and the prospect for the future was better. Mr J.B. Mathie seconded the motion, which was adopted.

20/01/1898 – Plan of the Shawsrigg no.2 pit at Larkhall owned by the Shawsrigg Fireclay and Enamelling Company of Glasgow abandoned for the main coal in November 1897 due to the coal being exhausted. The plan was supervised by Simpson and Wilson, mining engineers and surveyors of Glasgow and approved by J.B. Atkinson.

5/05/1898 – Letter from J.B. Atkinson, Glasgow, to B. Neilson, Shawsrigg Fire Clay mine, Larkhall, confirming that the mine has been opened up from the surface to work a piece of splint coal.

03/01/1902 – Hamilton Herald – Article discussing industry trade for 1901 … The work at the Shawsrigg and Birkenshaw Enamel and brickworks continues to be fair …

Below – 12/07/1902 – Airdrie and Coatbridge Advertiser – Shawsrigg Fireclay and Enamelling Company V Larkhall Collieries Limited. A dispute over rights to mine clay.

1905 – 1906 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co.. Ltd., 370 Eglinton St.

1907 – 1908 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co.. Ltd., 370 Eglinton St.

1908 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co. Ltd, 2 Oswald Street, Glasgow. The fire clay mine was called Shawrigg, Dalserf. 9 men worked underground and 2 above.

1908 – 1909 – Potter, Alexander (At Shawrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co., Ltd.); Ho. 15 Eskdale St., Crosshill.

Below – 1910 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay Works.

Below – 1910 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay Works.

Below – 12/04/1910 – The Edinburgh Gazette – Southhook Fireclay Company buys out the Shawsrigg Enamelling Company and they continue to trade as Southhook Fireclay Company Ltd until at least 1921. ( K. W Sanderson).

04/11/1910 – Edinburgh Gazette – Shawsrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co. Ltd (Incorporated under the Companies Acts, 1862 to 1890.) Notice is hereby given, in pursuance of sec. 195 of the Companies (Consolidation) Act, 1908, that a General Meeting of the Members of the above-named Company will be held within the Liquidator’s Office, 40 Gordon Street. Glasgow, on Wednesday the 14th day of December 1910, at three o’clock afternoon, for the purpose of having a report laid before them, showing the manner in which the winding-up has been conducted and the property of the Company disposed of, and of hearing any explanation that may be given by the Liquidator. Dated the fourth day of November 1910. David Cook, Liquidator.

1911 – Register of defunct Companies – Shawsrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co. Ltd, registered Edinburgh 1895. Voluntary liquidation April 1910. Undertaking and assets sold to Southhook Fire Clay Co Ltd. Final meeting return registered 15/12/1910.

1910 – 1911 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay and Enamelling Co., Ltd., manufacturers of white and coloured enamelled bricks, also white enamelled sinks, washtubs, closets, urinals, glazed sewerage pipes, &c, and other sanitary goods, 46 Gordon Street.

1910 – 1911 – Shawsrigg Fireclay & Enamelling Co., Ltd.

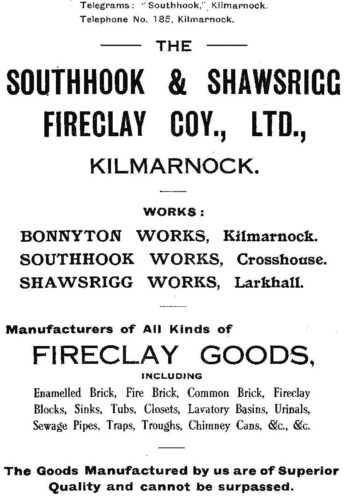

1911- 12 – Southhook and Shawsrigg Fire clay Co Ltd, Bonnyton Works, Kilmarnock.

1912-1913 – Shawsrigg Fire Clay Enamelling Co Ltd, 46 Gordon Street, Glasgow.

Below –22/10/1914 – The Scotsman – Court case – Contract for bricks due for export to Canada. Appeal – Southhook and Shawsrigg Fireclay Co Ltd V Thomas Bell Sons and Co.

30/03/1918 – Hamilton Advertiser – For sale … Messrs Southhook and Shawsrigg Fireclay Co Ltd, Kilmarnock. A trestle pithead frame about 35ft high. Nearly new.

23/06/1920 – Coatbridge Express – History of Dundyvan Brickworks. The employees of the Eglington Silica Brick Company Limited at Dundyvan Brickworks had their annual trip to Lanark on 5th June and a goodly company enjoyed the outing in the ancient burgh. Mr Wm. Donald, general manager, was present and at the conclusion of dinner, he made interesting reference to the history of their works.

Many trades, he said, that put out enormous efforts for the country during the war have had to pause and look around now that the war is over but with us it is different. Our trade is to supply the requirements of the steel trade and if the steel trade is busy, we shall be busy. Our duty is to see that the steel trade is never short of supplies of magnesite bricks. Another of our duties is to see that they get plenty of ground magnesite. And, as soon as we can, we should make them some chrome bricks, but we can’t do that while we are busy on magnesite bricks. When we do all we can, we are doing our bit. That is why you are all so busy, and you can understand from what I have said that we could have plenty to do for a long time ahead.

If we do all we can to keep the quality up to our highest level we will always have plenty to do, and something to spare for others in the trade. It doesn’t do to be the only arm in the trade. I find the other members real good friends, we have an Association – The magnesite Brickmakers’ Association – so that in addition to being members of your own Societies you are members of the Magnesite Brickmakers’ Society. Some of you will know, and others I think will be interested to know, that in 1871 there was another war in Europe. At that time it was Germany and France who were fighting over Alsace and Lorraine. Some of you know Alsace, where Metz is, opposite and near to Verdun, and others will know Lorraine where Strasbourg is. Germany won and occupied Paris, and France had to pay up. Now the tables have been turned and France has got back the Alsace and Lorraine countries taken from her.

Now, it was soon after and as a result of that Franco-German war that the Eglinton business first began. Land was got at Irvine harbour, and works were started to make chemicals that were in great demand. Limestone wait required, and the best stone was in County Antrim, but they couldn’t get enough, so my father went over to Ireland and out the Glenarm Quarries from Lord Antrim, built a pier, and built two steamers and got his limestone that way. In that limestone there were beds of flints and flints were bad for the chemical works, so that had to be removed from the limestone and soon a good many thousand tons of flints accumulated and had either be made into something or cleared out of the way. Well, as a result of that war steel was required, and the Blochairn and Hallside Steel Works were erected in Scotland and required silica bricks. My father knew that silica bricks were being made from flints on the Thames or were trying to be made, and be decided to make them on the Clyde. At that time Roberts had a foundry in South Wales where he made castings for brick machines like what we used to use. After giving his price for brick machines he offered to supply mills and to build stoves and kilns and the result was that he gave up his business in South Wales and came to Scotland with Norman and Jim Hannaford, who is now the foreman at Braehead. Roberts became the first works manager at Dundyvan, and the stoves and kilns were built by Mr Jamieson, the builder, to the plans that Roberts brought with him from South Wales. So that Dundyvan with all these Welshmen began as a colony of South Wales -a little New South Wales. That was in 1889. There have been ups and downs since then. At first, the steel trade of the Clyde was most affected with the Clyde shipbuilding. When therefore shipbuilding was busy, so was Dundyvan. After Roberts, the manager was Norman, then McGregor, the man with the one arm and then Dan Fraser. Fraser left in 1909 and it was that summer I came among you and became the works manager for six years. You will remember that my father was run over in January 1915. At that time I was far from well and he was Dundyvan every day. One morning he came down early and came in at No. 3 gate. The pugmen didn’t see him, and the pug came round the corner too quickly and my poor father couldn’t get past quick enough. A good many of you will remember my father and his great interest in all stages of manufacture. Sometimes he was too particular. But he was an exceedingly goodhearted master, and to all who knew him well, a good friend. He had a wide circle of friends. His death made it necessary for me to take up the reins, and I wasn’t long in seeing that with the altered circumstances of the war, calcined magnesite couldn’t be got. We would have to take cargoes of raw magnesite. Now the Dundyvan kilns at that time weren’t enough to do much calcining, burning of slap bricks and burning of finished, and 1 made up my mind that, I had to get hold of another Works. At first, I thought of Braehead but I soon saw that wouldn’t do what would be required without more plant first being erected at Dundyvan, so I leased Garnqueen, with the expectation that the kilns there would at least be able to do the calcining. The cost of upkeep of these kilns working at our high temperatures was very great for the work they did and the quality of the calcined magnesite produced was not nearly so good as what can be done at Dundyvan.

Relating the work done during the war Mr Donald said – By October 1916, we had become the largest makers in this country. In October that year, the steel trade wasn’t getting enough. So all the makers were called to the Ministry of Munitions and we were all asked what we could do. I promised to increase our production by a quarter within three months and I was asked to do it When that was done I was told one day that bigger supplies would be required. Could I do anything more! Well, I knew myself from the orders I had to refuse that more was required and I had been making enquiries about other works I could get. So I promised to come back in a week and let them know what could be done. Well,, when I came to Scotland the likeliest works were Shawsrigg Works, Larkhall, and the calcining kilns at Armadale. So I went back in a week. I remember it was 4 o’clock, on a Saturday afternoon, and I offered to double the production within two months if that was wanted, provided I could get more magnesite and provided I got some Garnqueen man back from the Army. That was promised, so I went ahead, the kilns at Shawsrigg were muffle kilns. These muffles had to be cleared out. The old set of kilns had to have their crowns put right. A brick machine had to be got to Shawsrigg and erected there and the mills had to be thoroughly overhauled. The works had been idle for two years and workers had to be got. The railway siding plant had to be extended, and the water supply was bad. A new pump had to be got, and so on. Also, we had to get another machine for Garnqueen so that we could depend on one always being right. We had also to get a second lightning crusher. The first lightning crusher had been got from Braidwood. The first machine came from London. Another was got from Irvine. The next was got from Gloucester. The next was got from Hull. And the next was got from Dublin. It was only by getting them second hand from where they existed, in works that were closed down, that the machinery could be got in time. Well, that gave us Dundyvan, Garnqueen, Shawsrigg and Armadale. At Armadale, all we did was calcining. Calcining was also done at Shawsrigg and Garnqueen, as well as slap bricks, and the first burning came to Dundyvan to be made into finished bricks. Later there wasn’t ever then enough, and we had to take the works at Kilmarnock. There was great excitement at that time. I had already entered into a contract to supply the French Government with three-quarters of a million magnesite bricks. Now Italy had joined the Allies and a representative from their Ministry of Munitions in Rome called at 45 Renfield Street and asked what we could do. I said quite simply that there was no limit to what we could de if we had enough magnesite and enough works to make bricks. So they asked me to supply a quarter of a million, delivering 50,000 in May, June, July, August and September in 1916. As soon as the arrangements were completed I went ahead at Southhook Works near Kilmarnock. One of the ‘Clan’ Line arrived from India. The raw magnesite was sent straight down there. Soon we began to get it into slap bricks and got them out too. So the production game began on a bigger scale. Well, we were up to time with the increased production. A wire came from the Ministry saying they had a wire from Italy wanting the bricks. Where were they? So I replied they were still in the kiln but the kiln door was down the previous day and we could have them packed up and despatched that week. That was how the thing went on and by September 1916 we had delivered the 750,000 to France and the bricks to Italy as well. That having been done the question was – What next? Well, the usual course of business is to execute orders but during the war, more questions than that had to be taken into account. The Germans settled this particular question for us. They sank two steamers with magnesite and made such havoc with their submarines that it was decided to restrict all exports and only to import magnesite to meet the demands of the British works. These were going to be very great, and it would be difficult to get all the supplies of magnesite from Greece that would be required.

It was decided, therefore, that Southhook and Shawsrigg Works and the Armadale Kilns would be given up and we would work away with Dundyvan and Garnqueen. In the meantime Dundyvan had grown. We had kilns 9, 10 and 11, and at Garnqueen we had built eight Newcastle kilns. At Dundyvan also we had added stoves 5 and 6. Since the Armistice we had the sale at Garnqueen of all the spare machinery and since then we have gone ahead at Dundyvan setting our house in order. That is what the steelworks themselves had been doing, and soon their orders came along again. This time with increasing orders. I made up my mind that to get the extra plant to give the increased production I wouldn’t go back to fireclay works, but would erect the most modern plant at Dundyvan, taking the erections decided on in their order of most importance. When we get erected all that has been purchased we shall have the best magnesite works in Great Britain.

There is a good old saying that “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”. More than that, however, it makes him less able to concentrate his attention to matters that his competitors pay attention to. All workers in any branch of trade have competitors in that same branch of trade either in the adjoining street, town, county or country, and it is just as necessary for each worker to consider his work in that light as it is for the employers to think how they can compete with other employers by the introduction of better machinery and plant. Employers depend on the machinery and plant being worked with the highest skill, and with the greatest economy. It is up to the workers to back up the employers and each to compete, with the workers who are doing the same job in the towns or in other countries. On the other hand, it is up to the employer to consider whether they can assist the workers by giving good working conditions, light and fresh air, protection from bad weather and warmth whenever necessary. In country districts it is often necessary to provide travelling facilities and housing accommodation. In towns like Coatbridge, where the workers have the choosing of the town councillors just as much and even to a greater extent than the employers have, they can introduce in their towns good education, good lighting, good tramway travelling facilities, good drainage, and in these days of town planning they can also introduce good housing schemes. In works that are situated in burghs or towns, the employer has taxes to bear that lighten the burden of the residential inhabitants and the workers, so that the inhabitants are all the better able to have the best conditions of life in their midst. It is mainly in their works themselves that the employers have their responsibilities, but my opinion is that it would be good for all employers if they gave their workers ground for development in allotments so that their interests in many of the things they have learned in their youth in country districts can be sustained. It is my hope that soon will be able to provide our workers not only with improvements in the working conditions at Dundyvan in many respects but also that at no distant date we shall have a field, part of which can be used as a football field either by the younger workers themselves or by the children of the older workers and in part of which the workers will have allotments that they can cultivate for the growth of vegetables and flowers. You will see from the coloured print of the Veitsch Company’s Works and buildings that they have a bandstand and laid out gardens for their employees. If they had not deployed their works first they would not have gone in for such wonderfully good developments in these directions. But their enterpriser before the war was really wonderful, and their spirit I hope to develop at our works in Coatbridge. The Veitsch Company are far away among the Austrian Alps. A panoramic view of these is exhibited. The works are five or six miles from any railroad and all their bricks and bags of magnesite have to be carted through a narrow valley to the Murs Valley where the lines run either east or west, either to Trieste, which is shown on the map, where shipments take place or towards Vienna where the railway lines distribute the goods to the various consuming centres. Shipments at Trieste are very difficult just now. Steamers take a long time to load. There are very few locomotives in the country. Such as there are, are using wood logs as fuel. You can imagine how much steam we could keep on our main boiler if we had only wood to burn. You can imagine how many carriages could have come from Coatbridge to Lanark today if the engine had logs of wood to burn instead of coal. I met a man recently, the representative of a very large Paris and London firm, who told me his principal was travelling from one end of Austria to the other, and also in Germany and that it was an ordinary occurrence for trains to stop between stations and for any timber near at hand, either fences or gates, or even parts of the carriages them, selves to be collected by the passengers so as to provide enough wood to steam the engine to the next station. My brother law is in that part of the world just now, and he tells me that the trains travel with only one-third of the usual carriages and that even though you have been travelling for two days and two nights in succession and are tired out, you can’t sleep in the trains for the shaking, and the jolting.

While they have plenty of food in the country districts, the food in the cities sells at ransom prices. They have no transport facilities. Coal costs anything from £15 to £20 per ton. You can imagine therefore, with no coal supplies how many kilns they can with logs of timber, and how many tons of dead burned magnesite and magnesite bricks they can supply. Of course, their competition is bound to come later, and it is for that reason that we are doing all that we can overtake to get erected good milling plant and good calcining plant so that we can do at our works all that they can do at theirs. When our plant is erected it will be up to the workers to work the plant with the highest skill. Your will compete with the labour of the Continent to do the work to the highest standard and as economically as possible. Wages will not come down until the cost of living is greatly reduced, but all workers should consider whether they cannot give a little more production. That may only be possible if the machinery or plant is altered so as to suit better the labour being done. The intention with us will be to give any proposal that is put forward by any of the workers in that way every consideration possible. Now, there is no use of speaking in generalities without giving an application to those general ideas, and I would like to refer in a few words to two matters that I know have been very much on the mind of our works manager. One of these has to do with the percentage of rejected magnesite bricks and the other has to do with fuel consumption.

I think the workers are to be congratulated on their having fixed an annual dance as you did last winter and also on the annual trip which you are beginning today. Whoever it was who originated the idea deserves credit. I shouldn’t be surprised if it was Maggie Toal and if it was, her name should be remembered and go down to posterity in the history of the works. I am more glad still that you are having such a fine day. I think the committee acted wisely in having a set dinner and afternoon tea, as they have done, and also in deciding that for this year they would have drives rather than sports. Perhaps for next year, now that the minds of the workers have become accustomed to the idea of an annual trip they will set themselves to begin to lay up for six months ahead of the trip, and if so they will be able to go further afield, either by train or by motor transport. There is nothing like providing well beforehand, and perhaps you will let me provide you with an idea about next year’s trip. That is, that it should be a trip either to the head of Loch Lomond or to Dunoon so that you could have a complete change of air and a good dose of sea breezes. I think you have been fortunate in choosing Lanark this year so that you can all get to know the county town of our county of Lanarkshire and to know the Falls of Clyde in the neighbourhood. This is one of the oldest burghs in Scotland. It was a place of residence of the Scottish kings before the English invasion of the times of Wallace and Bruce. Some of you may have been at Stirling and know the William monument. You can also see a statue of Wallace before the church steeple in the square. Wallace was one of the greatest men of Scottish history and though he wasn’t born here (he was born at Elderslie near Paisley) his young wife, Marion Bradfoote came from Lanark and it was at Lanark he first became prominent and famous. That’s a long time ago, seven hundred years ago and more, but it is undoubtedly due to his tremendous energy that the Scottish people retained their self-esteem and strength of character during a series of most trying experiences – The Scots came out well. I think it is a somewhat similar experience on much vaster lines that the whole people of this country of ours are emerging from. The recent war was a tremendous experience for all of us while it lasted. But I believe that we have all gained in strength of character and the best way to show that is in the work that we each of us do. Mr Lawson Scott, works manager thanked Mr Donald for his presence and interesting statement.

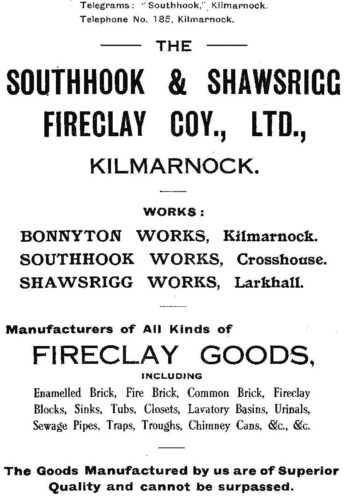

Below – 1923 – Kilmarnock trade directory – Southhook and Shawsrigg Fireclay Co Ltd, Kilmarnock. Works, Bonnyton, Southhook and Shawsrigg.

1923 -24 – Southhook and Shawsrigg Fire clay Co Ltd, Bonnyton Works, Kilmarnock.

Below – unknown date – Southhook and Shawrigg, Bonnyton Works product catalogue.